A people smuggler says that his clients are unaffected by the UK government’s proposal to send asylum seekers to Rwanda. He is met by Jane Corbin at his Turkish headquarters.

The night is falling as I make my way up the creaking stairs of a safe house in an anonymous alleyway in Istanbul, Turkey. I’m here to meet a kingpin in the people-smuggling trade – it has taken months to arrange, working through a trusted intermediary. It is the culmination of a BBC Panorama investigation into how thousands of migrants end up on the beaches of southern England claiming asylum.

The people smuggler is from the Middle East – young and softly spoken, smartly dressed in black. He has agreed to tell me about his business if we do not reveal his identity. His bodyguards discreetly keep watch outside the house.

I challenge him that smuggling people is illegal: “I know this is not legal,” he says, “but for me, it’s about humanity – that’s worth more than the law. We help people, we treat them well, we respect women – we don’t disrespect or hurt anyone.”

Nearly 2,000 people died in the Mediterranean Sea last year.

In April, the UK government signed a £120m deal with Rwanda to send some migrants, mostly single men, to Africa to have their asylum claims processed.

The government said the aim was to smash the business model of the people smugglers and stop record numbers of people making the dangerous English Channel crossing.

Already this year, more than 30,000 people have made the crossing in small boats, about as many as the whole of last year.

The people smuggler sends hundreds of migrants to the UK. He readily admits his trade is very profitable and says he runs it like a businessman.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s a whole family or an individual – each person pays the same price,” he says. “A trip to Britain will cost $17,000 [about £15,000] in total.”

So how can he justify putting people’s lives at risk in dangerous sea crossings in flimsy boats?

“Accidents can happen. We try and scare people to dissuade them,” he claims. “I say to them, ‘This road is dangerous and not worth it. You could die. And I tell his mum and his dad too.'”

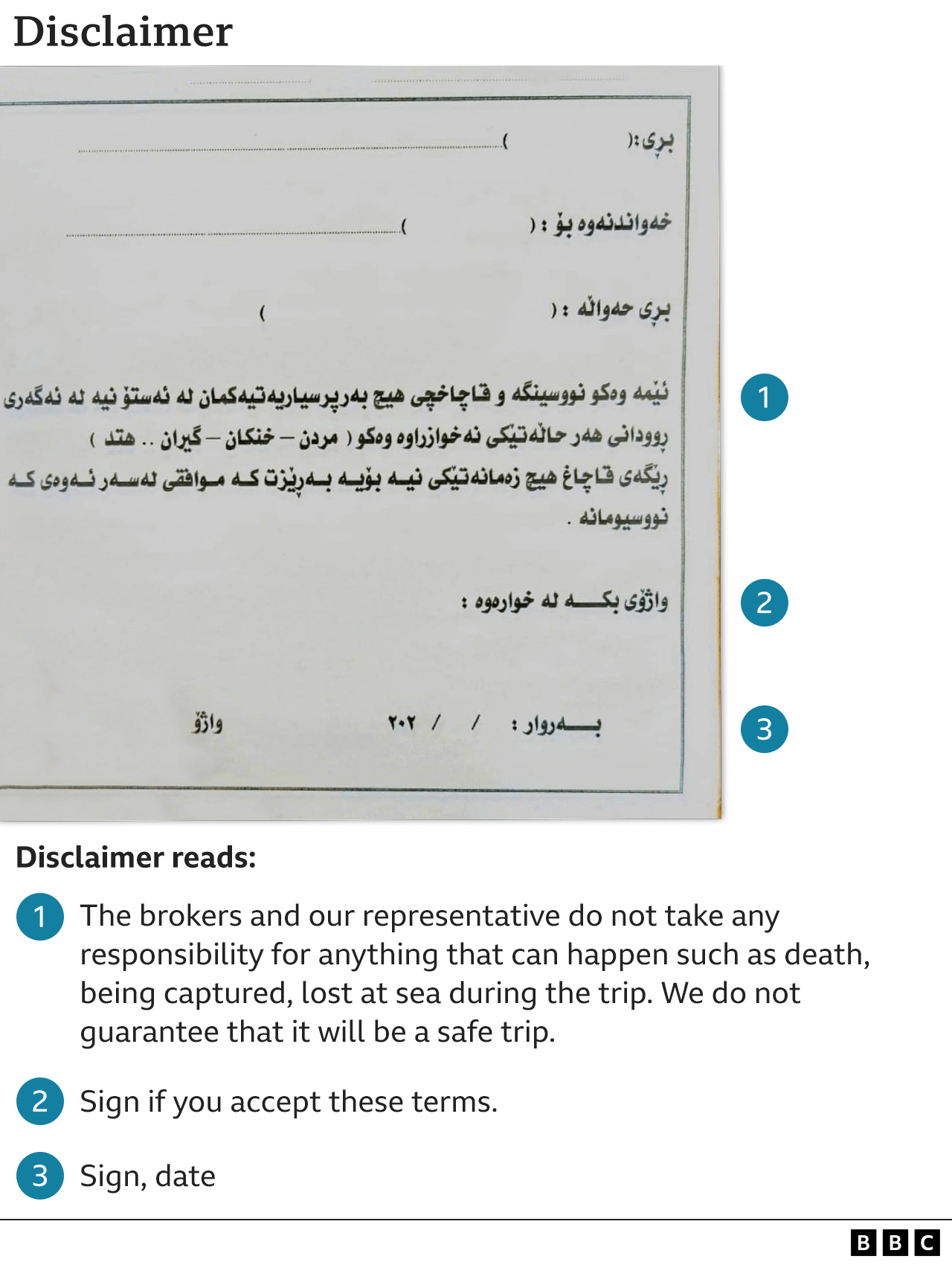

He shows us a form – a disclaimer he says he gets customers to sign, acknowledging the risks.

Istanbul is the gateway between Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe – and this black market trade is booming here.

Marketing is competitive. On social media, smugglers offer different rates depending on the destination.

There are fake passports and British driving licenses for sale. Even sample questions from British Home Office officials to prepare migrants for a grilling.

The people smuggler collects his clients in safe houses in this sprawling city, which is home to about five million refugees. They are packed into small rooms, where they can wait months while their passage is arranged. His gang brings them food and water from local supermarkets.

“We put them in a house and wait for everything to be prepared. And when it’s ready we take their phones so the cops can’t find out about us,” the people smuggler explains.

Then the migrants are taken in a van at night from Istanbul to the mountains. They walk in groups of six or ten, down to the Mediterranean, to one of the people smuggler’s boats.

They are bound for Greece or Italy.