Facial scarification was once popular across Nigeria.

Deep cuts, usually on both cheeks or the forehead, were carved on children by families and communities, mostly as a mark of identity.

The marks also held stories of pain, reincarnations and beauty.

The practice, however, has been fading away since a federal law banned all forms of child mutilation in 2003.

So the current bearers of facial marks are the last generation – their facial stripes as varied as Nigeria’s many ethnic groups.

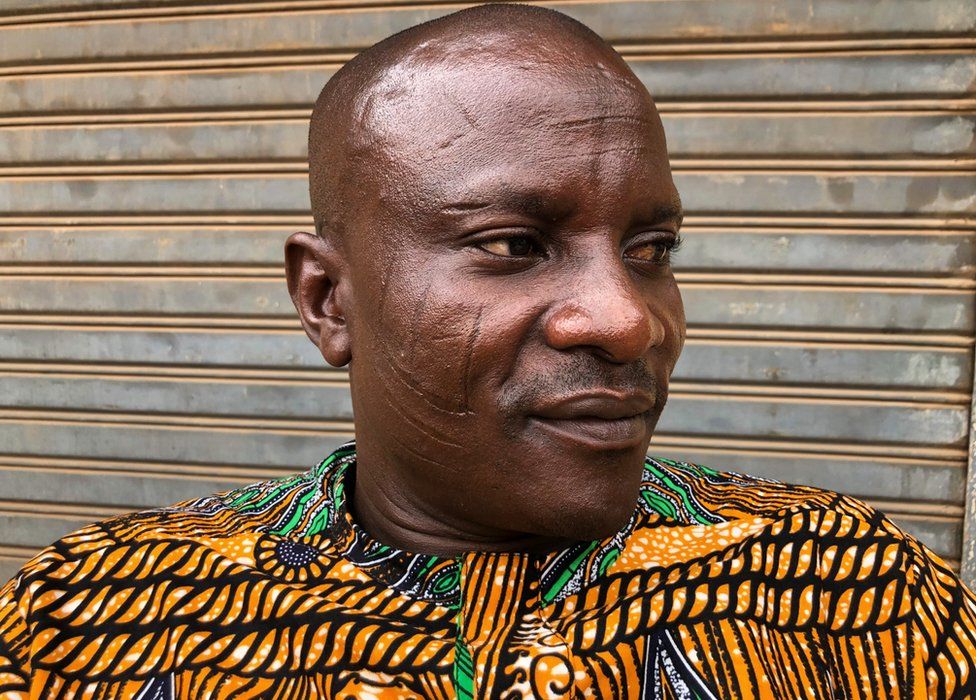

The 15 slashes on the face of Inaolaji Akeem (above) identify him as someone from the Owu kingdom in Nigeria’s south-western Ogun state.

Mr Akeem is royal-born, so he has long stripes on his face.

“It is like a football jersey,” he quips, adding that they made him popular in the local market.

On a serious note, Mr Akeem says he regards the scars as sacred, and does not believe people should mark their faces just for beautification.

This need for identification through facial marks was also strong in northern Nigeria, especially among the Gobir people of Sokoto state.

Ibrahim Makkuwana’s ancestors, pastoralists from Gubur in present-day Sokoto, did not have facial marks. But, he said, as they moved around looking for farming land, “they fought many battles and conquered many places”.

They then decided to make distinctive marks on their cheeks, “akin to the ones their animals had, which would help them in identifying their kinsmen during battles”, Mr Makkuwana says.

But there is also a distinction between the Gobirawas.

Those with six scars on one cheek and seven on the other have both parents from royalty. Those with six marks on both sides have only their mothers from the royal family.

Then there are the children of butchers, with nine scars on one side and 11 on the other, while those with five and six marks on either side trace their lineage to hunters.

As for fishermen, they have distinct marks drawn up to their ears.

Meanwhile, among the Yorubas and Igbos of southern Nigeria, some marks are linked to life and death.

There was a belief in their communities that some children were destined to die before puberty.

Known as Abiku and Ogbanje respectively by the two ethnic groups, these children were believed, by the Yoruba, to belong to a coven of demons living in large iroko and baobab trees.

It was common for women to lose several children at a young age in succession, and it was thought it was the same child, reappearing again and again to torment their mother.

Such children were then marked to make them unrecognisable to their spirit mates so they would stay alive.

Many of these infant deaths are now known to be caused by sickle cell anaemia, an inherited disorder common among black people.

Olawale Fatunbi’s four horizontal and three vertical marks were inscribed by his grandmother, who said he was a reincarnation of her late husband, who had those facial scars.

But Mr Fatunbi wishes he didn’t have them.

“I don’t really like them because I see it as child abuse but it is our culture,” he says.

“People call me Mejo Mejo from here to Lagos.

“My grandmother gave them to me because I am an only child,” she says.

Some scars are for beauty.

Foluke Akinyemi was marked as a child, a deep gorge on each cheek supervised by her dad at the hands of a local circumciser, who also did facial scarring.

“My father made a decision to give me a mark just for the sake of it and because he thought it was beautiful.

“It makes me stand out and I thank my parents for giving it to me,” she says.

Ms Akinyemi’s story is similar to that of Ramatu Ishyaku from Bauchi, north-east Nigeria, who has tiny whisker-like lacerations on both sides of her mouth.

“It is for beauty,” she says, adding that she also tattooed her face at about the same time.

As a girl, the whisker-like markings and tattoos were popular in her village and she and her friends went to the local barber to have them, she adds.

The marks on the face of Taiwo, who only gave her first name, are now fading but the memory of why she was carved still lingers.

When her twin sister died within weeks of her birth, Taiwo became ill and a traditional healer recommended marking her face to prevent her from joining her twin.

She became better within days of the scarification, she says, but that has not made her love the marks on her face.

“It makes you look different from anyone else – I’d rather not have any marks on my face,” she said.

There are also those like Murtala Mohammed in Abuja who don’t know the story behind their marks.

“Almost everyone in my village in Niger state had one, so I never bothered to ask,” he says.

Facial marks were inscribed by local circumcisers and barbers like Umar Wanzam using sharp blades.

He describes it as a painful experience done without anaesthetics.

Most of those like Mr Akeem, who were marked as children, agree it was right to stop facial scarification.

He did not pass on the tradition to his children even before it was outlawed.

“I love the marks but they belong to a different time and age,” he says.

Source: BBC