Renowned artist Galal Yousif successfully fled Sudan as conflict erupted earlier this year, carrying only a small backpack with a few essential belongings.

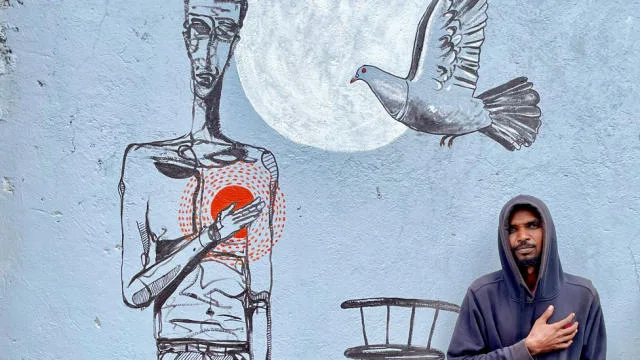

Capturing the turmoil of his journey, Yousif immortalized the experience in his painting “Man With a Heavy Heart.”

Originally created as a mural in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where Yousif arrived after a challenging journey in June, the painting has now been recreated on canvas in Kenya, where he has found temporary refuge.

The artwork depicts a powerful image of a man with a hand over his heart, surrounded by large circular red dots reminiscent of gunshot wounds.

A moon shines behind his head, and on the ground lies the backpack, symbolizing the profound losses experienced by the Sudanese people during the eight-month conflict.

Notably, the car key he initially packed serves as a poignant reminder of a hopeful return that never materialized.

In the heart of Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, artist Galal Yousif invites me into his home, which doubles as his studio, and shares the profound sentiment behind his creations. “I paint my pain,” he confides, unveiling his mission to transform personal experiences into a collective visual narrative that vividly portrays the extensive losses endured by many in war-torn Sudan.

His art serves as a poignant commentary on the toll of what he describes as a “useless war” that has claimed numerous lives. The conflict erupted in April, stemming from a dispute between two generals in the ruling junta—escalating into a clash between the army and the formidable paramilitary group, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The United Nations reports that approximately seven million people have been displaced from their homes due to the ongoing fighting.

Yousif recounts the ominous onset of the conflict, which he first sensed while working late in his studio near Sudan’s presidential palace. The fateful night of April 15 saw the gathering of troops nearby, prompting his decision to drive back to his family’s home in the northern part of Khartoum. He arrived just before dawn, narrowly escaping the outbreak of fighting that ensued shortly after his return.

In his dual role as an artist and storyteller, Galal Yousif aims to capture the shared experiences of loss and upheaval, offering viewers a powerful reflection on the impact of conflict on the lives of the Sudanese people.

“Chaotic days” followed, he says, as there was no water, electricity and little food – and he struggled to care for his elderly aunt and uncle and other relatives.

Every night he heard the sounds of planes and gunfire and could see large plumes of smoke descending over the city – prompting him to take the decision to leave.

He hoped it was a temporary move – managing to get bus tickets for all the family to head to their ancestral home in the city of Rufa’ah – around 150km (93 miles) south-east of Khartoum.

As the situation deteriorated and with his relatives too frail to travel further, Yousif realised that as a well-established artist he could do more to support them if he headed to Nairobi. So he set off with his backpack on public transport to Metemma, a town on the border with Ethiopia where thousands of people were heading.

A month later he managed to get a flight from Addis Ababa to Nairobi where he has found a community of other Sudanese artists who had also fled the once-thriving art scene in Khartoum.

According to Khartoum art curator Rahiem Shadad, around 35 of these artists are now in the Kenyan capital, including other big names like Bakri Moaz, Yasir Algari and Hani Khalil Jawdat. Others have settled in Cairo.

Mr Shadad, who owns Khartoum’s Downtown Gallery, representing many esteemed contemporary artists, tells the BBC his art space now lies in ruins.

A vast amount of artwork, including at least 165 framed paintings and 300 other pieces belonging to 60 artists, has also been lost, he says.

In recent months, the curator, who is also in Nairobi, has spearheaded numerous exhibitions of Sudanese art in the city.

He recently set up The Rest, a space for those in exile to live and work, with support from Nairobi’s GoDown Arts Centre.

Despite this warm welcome by Kenya’s art community, life is difficult for the Sudanese artists because of issues around asylum, lack of documents and their lack of substantial incomes.

“Some of these artists came with just $100 [£80] in their pockets,” Mr Shadad says.

Many of them are also deeply traumatised by their experience and losing their entire catalogue.

“Emotionally and spiritually, I am not OK,” artist Tibian Bahari tells me about not being able to return to Sudan where her father and sister still live.

Her aim is to keep Sudan – a “sacred and magical land” – alive through her work, which currently centres around depicting the country’s topography.

This determination comes down to her clothing.

“I always wear my jalabiya every morning,” she says, referring to the ankle-length, loose-fitting robe with wide long sleeves worn by both men and women in Sudan.

She feels a deep sense of “responsibility” to share “truthfully” her journey and map out the art of displacement and especially keep a space for Sudan’s women artists.

Many artists were part of the civilian protest movement that prompted the overthrow of Sudan’s long-time leader Omar al-Bashir in 2019. Afterwards, the army initially entered into a power-sharing arrangement with civilian groups, before seizing power and the decent into war.

These artists feel their dreams have been crushed by the conflict – and that the world has forgotten them in the wake of the conflict in Gaza.

In the last week, fighting has escalated. Yousif’s family has been under attack by the RSF in Rufa’ah.

Before the phone lines went down, he heard that his family, including his aunt, uncle and some of his siblings, had been forced out of their home by the RSF. They had managed to seek shelter at his grandmother’s house in city centre.

“For the second time, my family has lost our home, first in Khartoum and now in Rufa’ah,” he says, describing a city under siege.

“Nobody can go out,” he says, adding that they are virtually prisoners unable to move around or flee.

Like his painting, Yousif feels his heart continues to bleed.