Less than two months after he was re-elected president, Emmanuel Macron has lost control of the French National Assembly following a strong performance by a left alliance and the far right.

He had called on voters to deliver a solid majority.

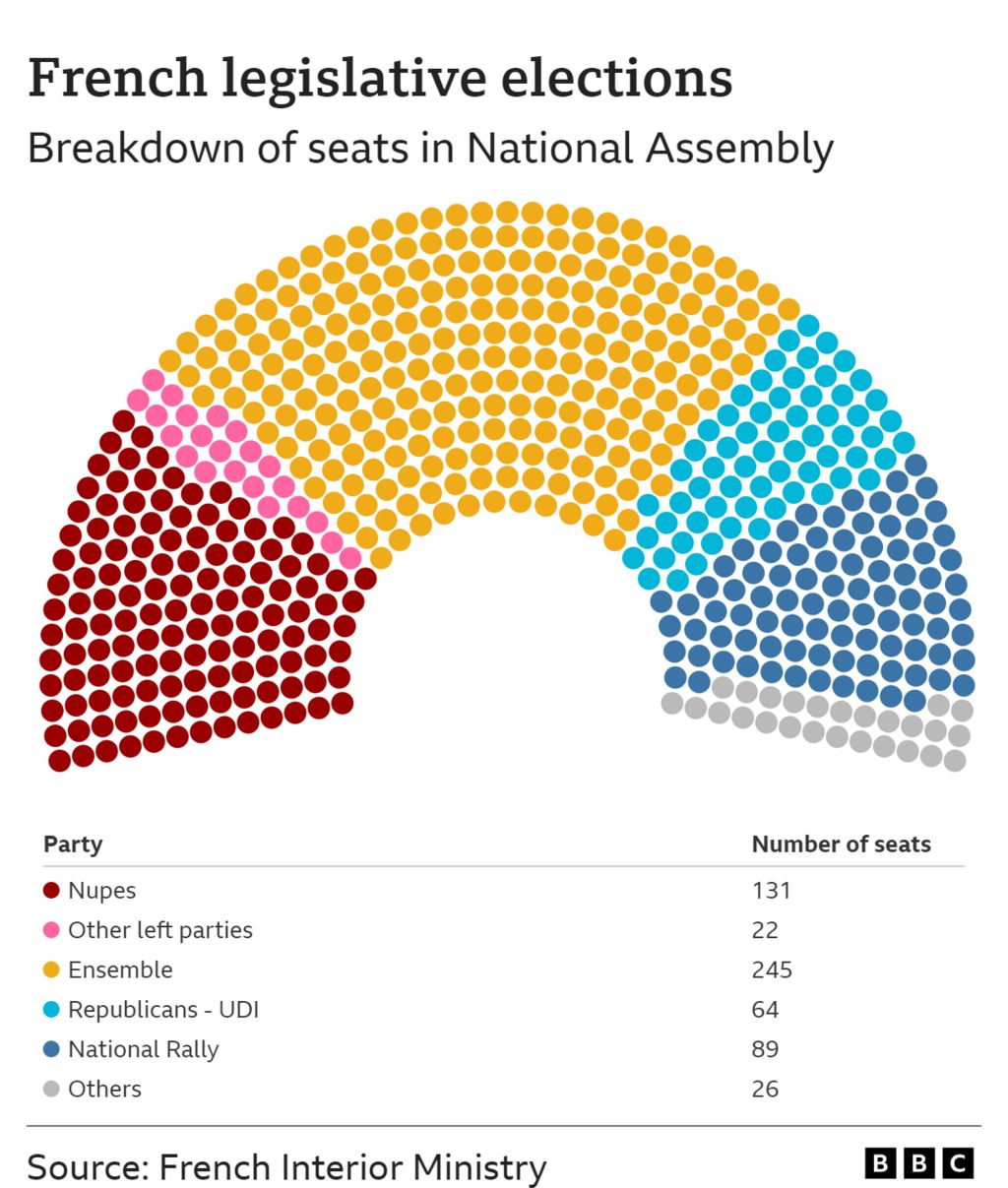

But his centrist coalition lost dozens of seats in an election that has left French politics fragmented.

The prime minister he had only recently appointed, Elisabeth Borne, said the situation was unprecedented.

A storm broke over Paris as she returned to her Matignon residence from a long meeting at the presidential Élysée palace to say that modern France had never seen a National Assembly like this one.

“This situation represents a risk for our country, given the risks we’re facing nationally and internationally,” she said. “We will work as of tomorrow to build a working majority.”

That seems a stretch when the two other biggest groups in the Assembly are not remotely interested in collaboration. Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire was adamant that France was not ungovernable, but said it was going to require a lot of imagination.

Far-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon was enjoying his success in bringing together mainstream parties from the left with Communists and Greens into an alliance called Nupes.

He told supporters that the presidential party had suffered a total rout and every possibility was now in their hands. His alliance now becomes the biggest opposition force in France, although opinion polls had indicated they could have performed even better.

Meanwhile, Marine Le Pen and her far-right National Rally party were also in jubilant mood after turning eight seats into 89. The people had spoken, she said: Emmanuel’s Macron’s adventure was over and he had been consigned to a minority government. Spokeswoman Laure Lavalette said the National Assembly now better reflected the views of French voters and her party would engage in “constructive opposition”.

If the prime minister was looking to the right-wing Republicans to help build a working majority, their message was not immediately encouraging. Party chairman Christian Jacob said the result was a “stinging failure” for a president now paying for cynically weaponising France’s extremes.

He’s not Jupiter any more, said Dominique Rousseau, professor of constitutional law, referring to an earlier nickname ridiculing Mr Macron’s supposed desire for power.

“For Mr Macron these five years will be all about negotiations and parliamentary compromise,” he told AFP.

Monday’s newspaper headlines ranged from a “slap” for Macron to a political “earthquake”, with fears of political paralysis and of France being “ungovernable”.

It was all so different in April, when he defeated Marine Le Pen convincingly and won a second term as president. He had more than 300 seats, but to maintain his outright majority he needed 289 – and fell well short with 245.

More than half of voters abstained, with a turnout of 46.23%. Young voters in particular were turned off by France’s fourth round of national elections since April.

Among the ministers to lose their seats was Health Minister Brigitte Bourguignon, who lost to her far-right opponent by just 56 votes. Green Transition Minister Amélie de Montchalin was also defeated, but another key figure, Europe Minister Clément Beaune, survived despite losing in the first round.

One of Mr Macron’s closest allies, the president of the Assembly Richard Ferrand, conceded victory to his Nupes rival Mélanie Thomin. Another casualty came on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, where a secretary of state, Justine Benin, lost her seat.

In a rousing speech to his supporters, Mr Mélenchon said the result marked the moral failure of “Macronie”, accusing the ruling party of enabling the far right by refusing to give clear guidance in seats where the left was running head to head with Marine Le Pen’s party.

In a tacit admission that he was unlikely to achieve his ambition of prime minister, the far-left leader said he was now changing his role in battle: “My commitment is and will remain at the front of your ranks until my final breath if you want.”

But as he was not running for a seat, he will not feature in the National Assembly.

Five years ago, Emmanuel Macron harnessed a wave of optimism, bringing in a fresh cohort of MPs from civil society. The new faces this time have emerged from Nupes and the National Rally.

Among the MPs elected for Nupes, which stands for New Ecological and Social Popular Union, is a hotel chambermaid who led her colleagues in a fight for better pay and conditions.

Rachel Keke had vowed to dance in the Assembly if she succeeded in defeating a former sports minister. “This will give other chamber-maids the confidence not to undervalue themselves,” she told French radio.

A voté ! 😊#legislatives2022 #circo9407 pic.twitter.com/Xcn7HYybo3

— Rachel Keke (@KekeRachel) June 19, 2022

Which reforms are at risk?

President Macron has promised to tackle the cost of living crisis, but his rivals have very different ideas on how to go about it. His big-ticket proposals were reforming benefits, cutting taxes and raising the retirement age gradually from 62 to 65.

His pension age reform will be particularly hard to get through, although he will attract support from the Republicans.

Then there are proposals to move towards carbon neutrality and full employment. And he recently offered a “new method” of governing with greater involvement from civil society, proposing a National Council for Refoundation made up of local people to make France more democratic.

Source: BBC