This is the moment history stops; for a minute, an hour, for a day, or a week; this is the moment history stops.

Across a life and reign, two moments from two very different eras illuminate the thread that bound the many decades together. At each a chair, a desk, a microphone, a speech. In each, that high-pitched voice, those clipped precise vowels, that slight hesitation about public speaking that would never quite seem to leave her.

One moment is sun-dappled, though the British people were suffering through a terrible post-war winter. A young woman, barely more than a girl really, sits straight-backed, her dark hair pulled up, two strings of pearls around her neck. Her youthful skin is flawless, she is very beautiful. A life opens out ahead of her.

She pledges that life to her audience around the world. She tells them: “I shall not have the strength to carry out this resolution alone.” And she asks for their company in the years to come.

The other speech is more formal. More than seven decades later, on the 75th anniversary of the day the war in Europe ended, she sits behind a desk, a picture of her father, the late King, in uniform, to her right.

Her hair – still pulled up – is white now. She wears a blue dress, two brooches, and three strings of pearls. The many decades have left their mark, but her eyes still sparkle and her voice is still clear. The desk is practically empty but for the photo and to the right, in the foreground, a dark khaki cap, with a badge on its front.

“All had a part to play,” she says of a long-ago war.

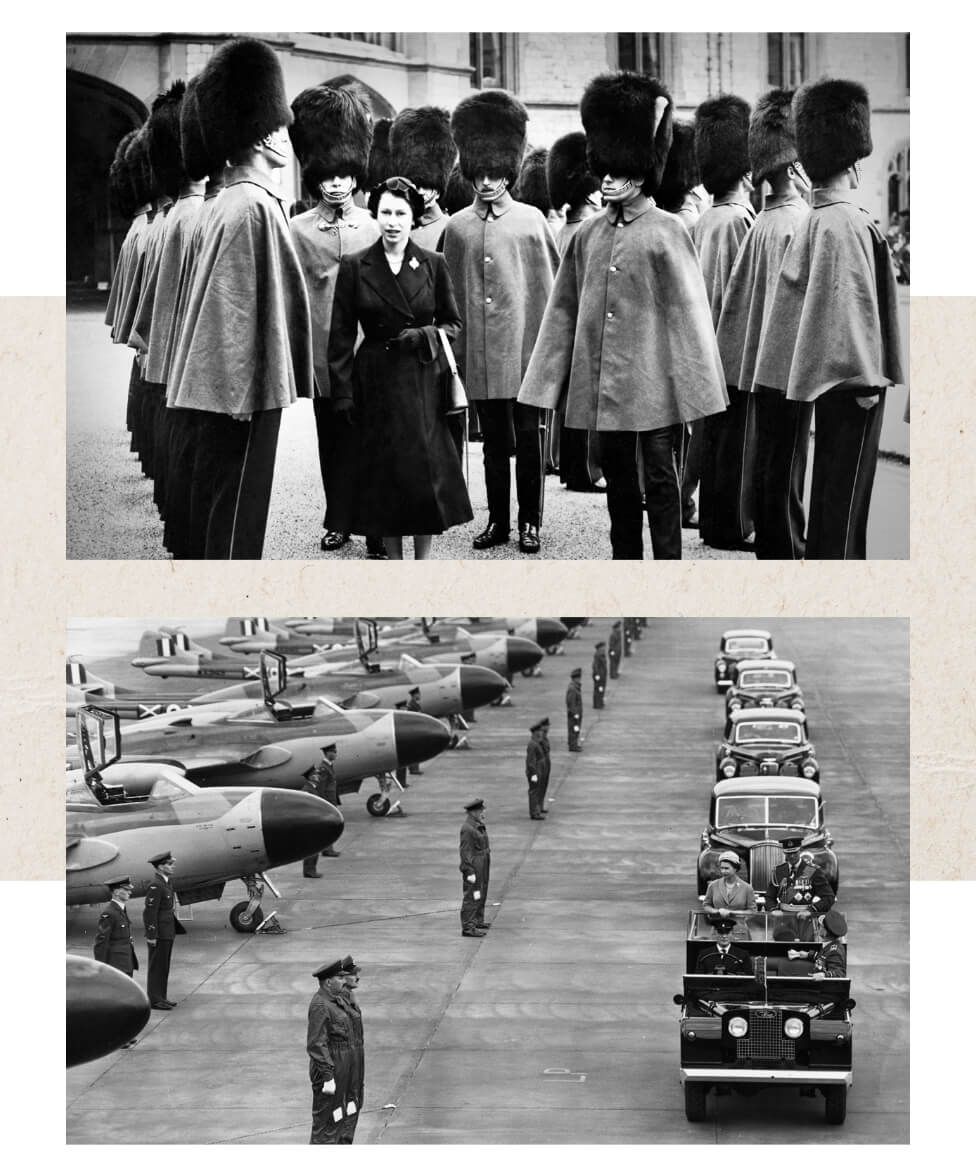

The cap belonged to Second Subaltern Windsor, of the Auxiliary Territorial Service; the young Princess Elizabeth nagged her adoring father to allow her to join, so she could serve in uniform, even as the war that defined her – and for many decades her nation – drew to an end. Now, 75 years on, the cap has pride of place as she speaks to the nation on the anniversary of a great and heroic victory.

The cap is a simple reminder of what she admired most – service: the service she offered that golden day decades beforehand, the service she saw in her formative years as nation, Commonwealth and Empire gave life and limb so that others could be free; the service that she believed lay at the heart of the Crown she inherited and devoted her long life to.

Three decades on from that vow of service, she would allow herself a rare moment of public introspection; “Although that vow was made ‘in my salad days when I was green in judgement’,” she told the Guildhall on her Silver Jubilee, “I do not regret or retract one word of it.”

Over the decades she spoke little, and revealed even less, about herself in public. She – a child of the broadcast age – never gave an interview. Once or twice she would be filmed “in conversation” with a trusted friend, talking amicably about something uncontroversial, like the royal jewellery collection.

Her words would be scoured for a hint of controversy or an opening into her character. But she was too careful – and her friends too loyal – for anything important to slip out.

She did not neglect the medium that came of age as she did. It was her decision to allow her coronation to be televised, her decision to televise the Christmas Broadcast, and her decision to speak live to the nation after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. “I have to be seen to be believed,” she would say.

Broadcast and newspaper coverage, the endless pictures of her in well-chosen gowns and dresses – these were part of what it was to be Queen, part of the job she had pledged her life to. Talking about her feelings publicly was not.

And she came from a generation – and from a nation – that did not feel the need to share its feelings. The nation would change. She would not.

Here fate and character would collide. It was her fate to take the Crown as the country moved into far-reaching change. But the Queen was open about her liking for tradition, for the ways things had always been done, and her dislike of change.

Her heart was in the countryside, and there, with horses and dogs and amongst those who loved animals as she did, was the reassurance of a place that changed incrementally, if at all.

“I find that one of the sad things,” she would say in the late 1980s, is “that people don’t take on jobs for life, they try different things the whole time.”

Monarch and monarchy fitted hand-in-glove; a sovereign who relished tradition leading an institution established upon it.

Beyond the palace gates, a whirlwind of change would transform Britain. She came to the throne at a tipping point in British history. Victorious in – but exhausted by – war, the country was no longer a global, military, or economic power.

The rise of trade unions, the collective provision of services, and the creation of a universal welfare state signalled a sea-change in the organization of state and economy. The stately withdrawal from Empire became a hurried exit.

As her reign progressed, the old order – Church and aristocracy, the gradations of class and knowing your place – crumbled. Financial success and celebrity overtook accident of birth as a measure of societal achievement.

Consumer goods – fridges, washing machines, televisions, and vacuum cleaners – transformed homes and social lives. Women joined the workforce; old working-class communities were swept away with the slums that housed them; a society once cohesive and homogeneous became mobile, atomized, and diverse, uprooted from old certainties and loyalties.

There was some change at the Palace too, especially early in the reign – the end of the debutante “season” would mean the daughters of the “best” families would no longer be presented at court, and fresh faces were seen among those invited to lunch and dinner, and television meant Britons could see their Queen and how she lived – first for the Christmas broadcast, then for a full-length documentary in the late 1960s.

But this was changed with a very small “c”; as her seventh decade on the throne drew to a close, the rhythm of the monarchy remained one which would be recognizable from the first, one which her father or even her grandfather would be unsurprised by Christmas and New year at Sandringham, Easter at Windsor, the long summer break in Balmoral, Trooping the Colour, Royal Ascot, the Investitures, the Changing of the Guard, Remembrance Sunday.

Changing times – riding the London Underground in 1969, and preparing to deliver her televised Christmas message in 1967, the first to be delivered in colour.

When change pressed in all around, she resisted. Her fate was to inherit the crown as the country stood on the cusp of change, and to reign as change swirled around the palace. Her character dictated that she would not change with it, would not bend to fashion. That resistance, that deep appreciation – love, even – of tradition, was her greatest strength, and led to perhaps her greatest test and gravest crisis, as her family unravelled.

Family always came second to the Crown. When her first two children, Prince Charles and Princess Anne, were little more than toddlers, they were left behind – as she and her sister Princess Margaret had been left behind by their parents two decades earlier – as the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh went on a six-month world tour.

She was not an unfeeling mother, but she was a remote one. The Crown and its responsibilities had come to her when she was just 25, and she took those responsibilities very seriously. Many decisions about the children were delegated to the duke.

Three of her four children’s marriages would end in divorce. She believed in marriage, it was part of her Christian faith and her understanding of what knitted society together. “Divorce and separation,” she once said, “are responsible for some of the darkest evils in our society today.”

No doubt that view, held by many in the late 1940s, mellowed as the years went by. But no parent relishes seeing their child’s marriage fail. The Queen’s self-proclaimed “annus horribilis” in 1992 saw the separation of the Duke and Duchess of York, the divorce of Princess Anne and Captain Mark Phillips and the separation of the Prince and Princess of Wales.

“A low point in her life,” wrote one biographer, not because of what had led to the rare public admission of tough times, “but because of the lack of gratitude, even derision, with which her 40 years of dedication appeared to have been crowned.”

Her first decade had passed in a dazzle of adulation, at home and abroad. Vast crowds turned out for her on international tours. Back home, some proclaimed a new Elizabethan Age, although the Queen was clever enough to immediately disavow it.

The 1960s saw a slow cooling off – the Queen was more involved with her family, the novelty of a new monarch had passed, and the generation of the post-war baby boom now coming of age was gripped by different passions than their parents. The 1970s and 80s saw no let-up in her service, but the focus of some Royalty enthusiasts – and the media – shifted to her children, their marriages, and their partners.

By the mid-90s, the monarchy seemed to some to be out of touch with the popular mood; in the newspaper comment columns, there was a direct criticism of the Queen, and contemplation of the monarchy’s future. Her reign at times seemed associated with another epoch. What was her place – and the monarchy’s – in the new “Cool Britannia” and the informal style embraced by Tony Blair? How did the Palace – repository of tradition – fit in with the popular demand for change expressed in Labour’s crushing election victory?

Just months after that victory, one hot August night in Paris, came the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. A broiling carpet of flowers soon stretched out in front of Kensington Palace. The flag pole above Buckingham Palace remained bare. Many in the nation found themselves desolate at the loss of the Princess.

“Show us you care, Ma’am” bayed the Daily Express headline. “Where is our Queen? Where is her flag?” demanded the Sun. For five long days, the Queen remained in Balmoral, seemingly unaware of the spasm sweeping parts of the country. Perhaps, as the Palace would brief afterward, it was to protect and console the young Princes William and Harry.

But given her character, that deep dislike of change appears to have driven the decisions taken at the time; Balmoral was not to be interrupted, no flag ever flew from Buckingham Palace in her absence, and the Royal Standard never flew at half-mast.

It was a terrible misjudgement. She hurried back to the capital, back to Buckingham Palace. She stopped to look at the flowers piling up all around. “We were not confident,” one former official told a biographer, “that when the Queen got out of the car, she would not be hissed and jeered.” It was that bad.

She had refused to broadcast at first, then yielded, then agreed to speak live. She spoke to the nation, just before the BBC Six O’clock news. She – who had once driven broadcast executives to despair with her wooden delivery – barely had time to prepare.

Her performance was flawless, her speech brief but perfectly pitched. She spoke of “lessons to be learned”; she spoke “as a grandmother”; she spoke of the “determination to cherish” Diana’s memory.

It was a triumph, pulled from the jaws of deep crisis. The poison swirling around the Royal Family, around the Palace and around the very institution of the monarchy, was drawn. Once in her reign – just once – fate and character had collided with near-disastrous consequences.

They would combine more happily in the Queen’s international role. By the time of her death, she had not toured for many years. But for decades she was not only a global celebrity like no other but also a subtle instrument of influence.

Nothing would compare to the first dazzling decade of her reign, before television made her image commonplace and her tours accessible from the living room. On her long 1954 tour of Australia, two-thirds of the country is thought to have turned out to see her; in 1961 two million people lined the road from the airport to the Indian capital Delhi; in Calcutta three-and-half million would stand and wait to see the daughter of the last Emperor.

Fate would dictate that she would oversee the long twilight of the Empire, though not once did the Queen attend a flag-lowering ceremony. Many times in the 1950s and 60s, a member of the Royal Family would stand as the Union flag came down over a former colony, the national anthem playing one last time.

A determination that something should emerge from the imperial family that she had pledged to serve, would mean that she would build a new association on the ashes of Britain’s imperial legacy.

In palaces and houses dotted across the capital and the country, lived her blood family. Across the world was spread her territorial family – a group of wildly diverse nations, vast and tiny, rich and impoverished, republics and monarchies – that she charmed and cajoled and nudged to remember what bound them together, and what together they might achieve.

International tours were taken on behalf of the government of the day; they were tools of foreign policy – if not explicitly, then on the understanding that the Queen’s influence would be beneficial to the relationships between Britain and the places she visited.

It looked glamorous – the Royal Yacht, the Queen’s Flight, banquets, and galas – and before international air travel became commonplace, it was an extraordinary experience. But it was always hard work, long days and weeks of receptions, exhibitions, openings, lunches with officials, state dinners and speeches given and listened to patiently. Those who have observed a royal tour find it hard to imagine it is any fun for those at the heart of it.