Ten years ago when a 19-year-old Delhi woman was found gang raped and murdered in the fields of the neighbouring state of Haryana, it was described as a “rarest of rare” case.

Indians were shocked by news reports which detailed the brutality to which the teenager – named Anamika in court documents as her real name could not be revealed under Indian law – had been subjected.

Three men, arrested for the crime, were found guilty and given the death penalty by a trial court in 2014 and the Delhi High Court confirmed the sentences a few months later.

But on Monday, in a stunning reversal, the Indian Supreme Court set the men free, saying there was no “cogent, clinching and clear evidence” that they had committed the crime.

The three-judge bench raised serious questions about the police investigation, criticised the sessions court for “glaring lapses” in the trial and said the judge had acted like a “passive umpire”.

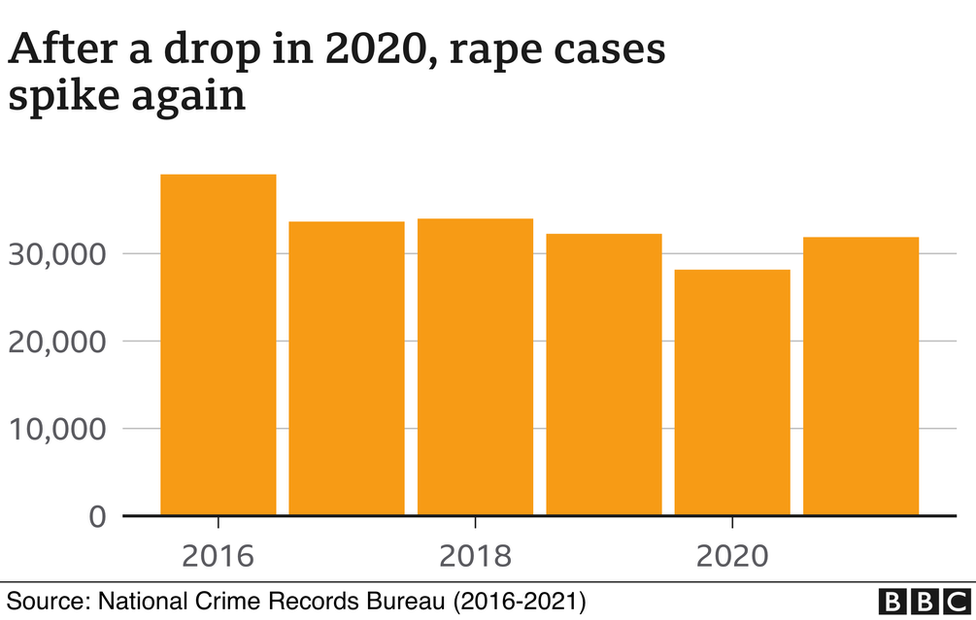

The decision has angered the victim’s parents, shocked activists and lawyers and led to outrage on social media in a country where tens of thousands of rapes are reported every year.

“This is what justice looks like in India 2022,” one Twitter user wrote, sharing a photo of the woman’s dejected father.

Some compared the top court’s decision with a recent order by the Gujarat state government to release convicts who were serving life sentences for the gang rape of Bilkis Bano, a pregnant Muslim woman, and the murder of her relatives during 2002 religious riots in Gujarat state.

Anamika’s father told me that his “hopes of getting justice were dashed in minutes”.

“We had waited for 10 years for justice. We had faith in the judiciary, we believed that the Supreme Court will confirm the death penalty and my daughter’s killers would be finally hanged,” he said.

The 19-year-old lived in Chhawla, a lower middle-class rural area in south-west Delhi. In January 2012, she started a job at a call centre in Gurgaon, a suburb of the capital, and was the sole breadwinner for her family.

“She had just received her first salary and was thrilled,” says anti-rape activist Yogita Bhayana, who has been supporting the family in their fight for justice for the past eight years.

On the night of 9 February 2012, Anamika was returning home from work with three friends when she was abducted by men in a red car.

The gruesome crime made headlines in India after her partially burnt, horribly mutilated body with signs of torture was found four days later.

During trial, the prosecution argued that the case against the accused was watertight – they said they had found the wallet of one of the three men at the crime scene, that the suspects had confessed to the crime and had led the police to the body and helped recover the victim’s clothing.

DNA samples collected from blood stains, semen and hair found in the seized car proved that the accused and the victim had been in the vehicle, they added.

The trial court convicted the men and gave them the death penalty two years later. While confirming their death sentence, the high court described the accused as “predators”.

But Monday’s 40-page Supreme Court order, authored by Justice Bela Trivedi, questioned the evidence presented by the prosecution and said it was possible that it had been tampered with.

Pointing out a “number of inconsistencies and contradictions in the evidence of the police and in the testimonies of the formal witnesses”, the court said:

- The accused were not identified in court by the victim’s friends or a male witness who had tried to fight the kidnappers.

- The Delhi police claim about the “discovery of incriminating articles such as a piece of the car’s bumper and wallet containing documents of one of the accused” were not seen in the first pictures from the crime scene.

- Haryana police, who had reached the scene first, did not mention these items in their report.

- The items were not mentioned in the seizure memo of the investigation officer.

- A phone the police recovered was never shown to the woman’s father to confirm whether it really belonged to his daughter.

- It was not conclusively proved that the red car seized by the police was the same in which the crime had been committed.

- The circumstances of the arrests were questionable.

- Non-examination of some of the accused had “created a cloud of doubt”.

The court also said that the evidence taken from the car was sent for forensic examination on 27 February – almost two weeks after it was seized. “Under the circumstances, the possibility of tampering with the samples could not be ruled out,” she wrote.

Acknowledging that “if the accused in a heinous crime go unpunished, a kind of agony and frustration may be caused to the society in general and to the family of the victim in particular”, the order said that the “prosecution has failed to prove the charges beyond reasonable doubt and we have no alternative but to acquit the accused, though involved in a very heinous crime”.

The BBC has emailed top Delhi police officials for comment.

Charu Wali Khanna, the lawyer for Anamika’s family who assisted the prosecution, told me the order would be challenged in the Supreme Court with a review petition.

“This judgement is very vague and it raises these hyper-technical issues. It says the evidence could have been tampered with, but it does not indict the police,” she said.

“The order says there was no clinching evidence, but they disregarded a lot of evidence that was against the accused.”

Anamika’s father, who works as a security guard at a school, told me he had gone to the court straight from work on Monday after his night shift.

Ms Bhayana, who waited outside the court with the parents while the judgement was read out, spoke of the anger and disappointment they felt.

“I’m heartbroken, I don’t have the words to explain how I feel. So you can imagine how the parents must feel,” she told me.

Ms Bhayana said she “didn’t even have 1% apprehension” that something like this could happen and had been assuring the family that this was “the end of the road” in their fight for justice.

“But it’s all collapsed around us. When the lawyer messaged me informing about the order, my first reaction was of disbelief. I thought I must’ve misheard.”

Ms Bhayana says if the Supreme Court had concerns about the investigation, they could have reopened the case, ordered another investigation, or handed over the case to the federal police.

“The fact is that a young woman was gang raped and brutally murdered. The court must provide some kind of remedy to her family,” she says.

Anamika’s father, meanwhile, is bewildered.

“Mere upar to vajr gir gaya [I have been hit by the bolt from the sky],” he told me.

“What has the Supreme Court done? The courts did not have any doubts for 10 years. So how did everything suddenly become a lie?” he asks.

“Everyone says India is not safe for its girls. After this court order, no girl in India will be safe. This will embolden criminals further,” he says.

Source: BBC.com