“Of 500 patients who have come to the clinic since the morning, 200 have died” – that is the blunt assessment of Muhammad Gul, a staff member at a tiny clinic in Gyan, in eastern Afghanistan.

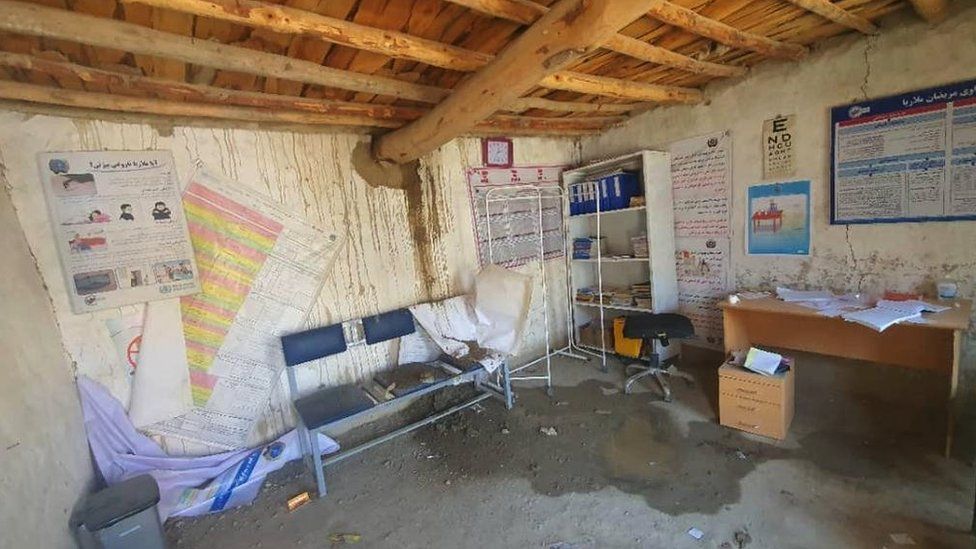

The facility has just five beds, but Tuesday’s earthquake left even these meagre resources unusable.

“All the clinic’s rooms have been destroyed,” Mr Gul told the BBC.

He said a helicopter had airlifted a handful of patients from the remote district in Paktika province to cities for treatment, and two doctors were manning a makeshift outdoor clinic to try to treat people who had nowhere else to go.

The generator supplying power has only a limited supply of fuel, and the help promised by other provinces has yet to materialise.

Meanwhile, casualties keep on arriving.

“There are dozens of people who need immediate medical help. I don’t think they will survive the night,” Mr Gul added.

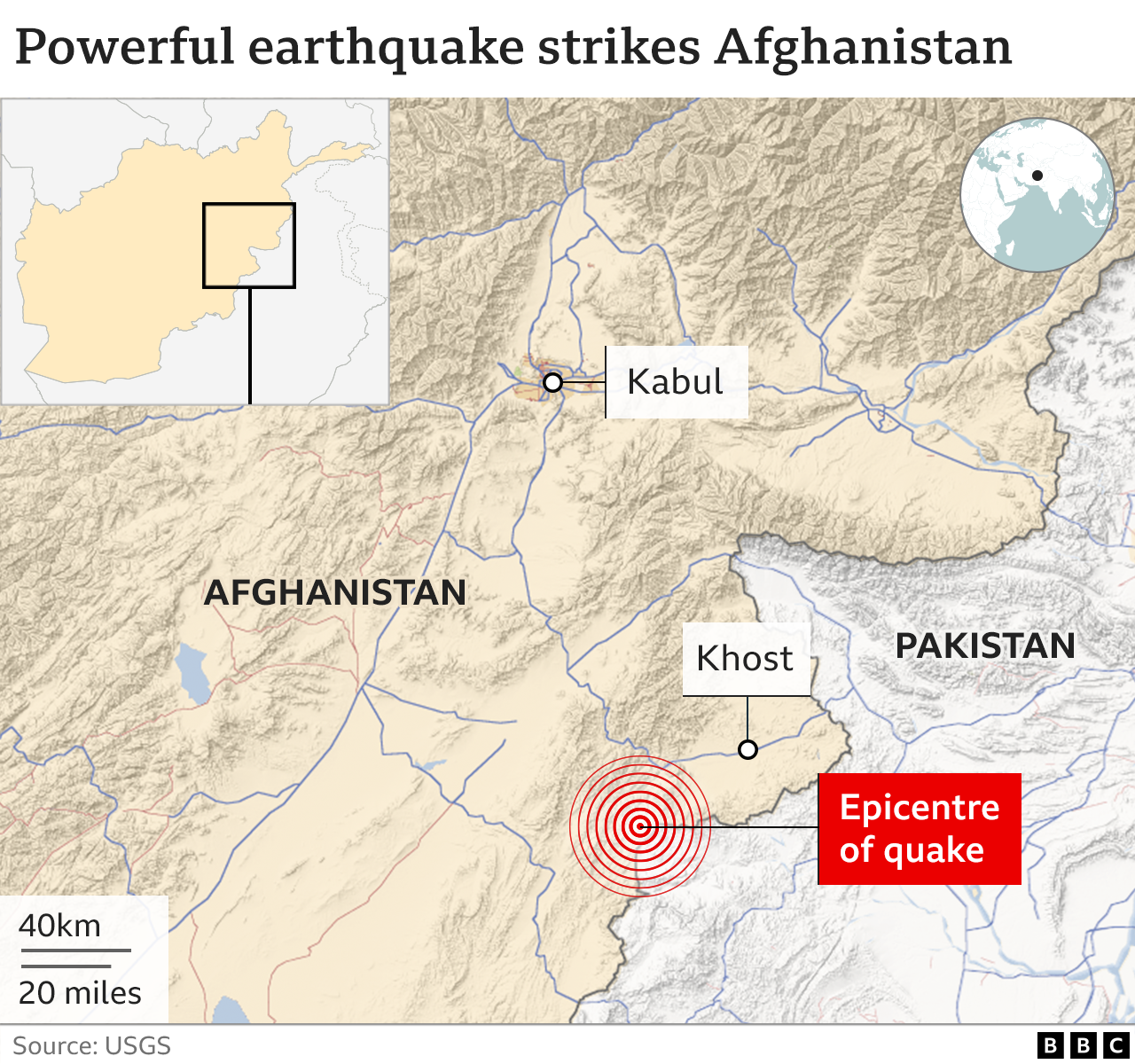

The earthquake struck impoverished hilly areas with weak buildings, ill-equipped to handle the shock. Hundreds of houses have been destroyed and there have been landslides.

Gyan is one of the worst-hit areas. Many people remain trapped under the rubble.

International development agencies set up the clinic there a couple of years ago. It was meant to deal with minor health conditions and refer people to hospitals in major cities for more significant treatment. It had no accident and emergency department.

Since the hard-line Islamist Taliban took power across the country last August, many international aid agencies have left the country. The medical system has been dealing with severe shortages of supplies and staff.

When the Taliban’s acting district governor toured Gyan on Tuesday, people shouted at him, telling him to leave, a volunteer from a neighbouring district told the BBC.

“The Taliban are not capable of dealing with this disaster. There is no system in place,” the volunteer, who did not want to be named, said.

“And we cannot be hopeful for international help. The world has forgotten Afghanistan.”

Even before the Taliban takeover, the country’s emergency services in its larger towns and cities had limited capacity to respond to natural disasters. There were few aircraft and helicopters available.

According to Paktika’s medical authorities, there is a severe shortage of painkillers and antibiotics in the region.

One of the doctors at Gyan’s makeshift clinic went there from the neighbouring district of Ghazni to volunteer.

There was one young father who had suffered a chest fracture, and who was crying and asking for his family members, including his children, the doctor said. “He asked me to let him die if they were not alive.”

Most of the patients were men, as women and children were less likely to be able to free themselves from debris and destroyed buildings, the doctor said.

Some children were at the clinic without their parents, including a severely injured boy of eight.

“He was begging people to go and help his parents and siblings who were trapped in their house,” said the doctor.

“He then overheard someone tell me that they were all dead, and he cried and fell unconscious.”

The BBC has been shown photos of people with open wounds waiting to be seen at the clinic.

Bodies are reported to be lying on the ground in the area.

There are no official aid workers present, but people from neighbouring areas are arriving to help with rescue efforts.

One volunteer rescue worker from the nearby city of Urgun was helping to pull trapped people from the rubble.

He said he had found 40 bodies since the morning, mostly of young children.

But even for those who did make it out of the devastation alive, the immediate future looks bleak.

“We don’t even have access to clean water to wash the wounds and it’s extremely hot,” the volunteer doctor said. “I think soon, infection will spread.”