Former inmates have spoken to the BBC about being systematically raped and tortured in Russian prisons.

Leaked footage of such abuse was circulated by an insider last year, and now victims have told the BBC why it happens and how they are fighting for justice.

Warning: This article contains graphic images and descriptions of sexual abuse and violence

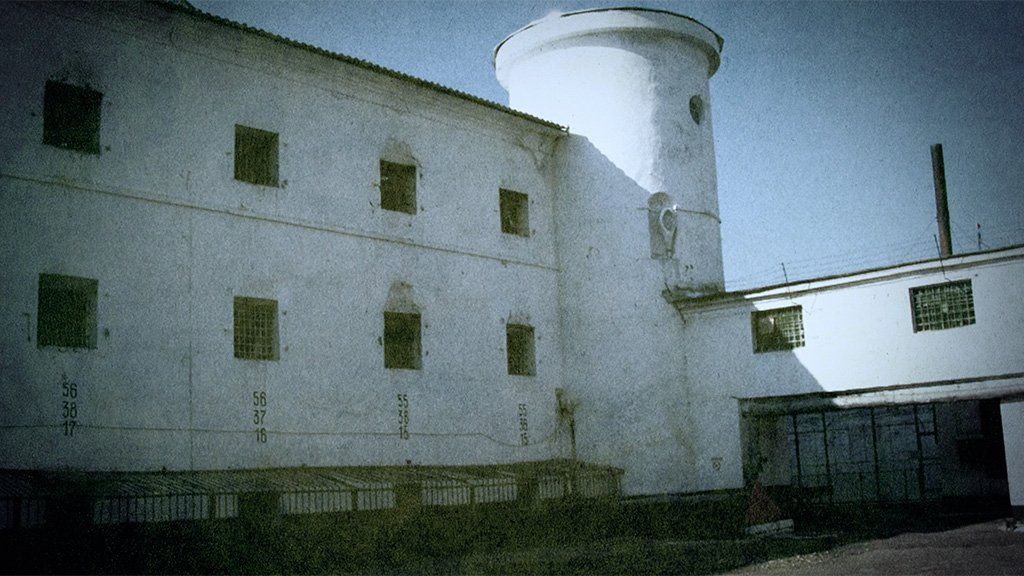

Saratov prison hospital, in south-west Russia, came to public attention last year when videos of horrifying prisoner abuse were leaked to a human rights organisation and reported on by the international media.

Alexei Makarov knew its reputation before he was transferred there in 2018 as part of a six-year sentence for assault. Prisoners who are sent to Saratov from other jails in the region have complained that medical grounds were fabricated so they could be tortured behind closed doors.

Russian prisons have almost no independent oversight, and prison hospitals – with their health quarantine rules – even less so.

Makarov was genuinely unwell – he had been diagnosed with TB – and hoped he would be spared. But he says he was raped twice during his time there.

Victims and experts say the abuse – which Makarov and others have been subjected to – is always sanctioned by the prison authorities, and is used to blackmail inmates, intimidate them, or to force confessions.

High-profile leaks of damning footage have forced the Russian government to respond to the country’s torture scandal. Torture was reported in 90% of Russia’s regions between 2015 and 2019, according to independent Russian media project Proekt.

But action has been slow.

The BBC has analysed thousands of court documents dating from that period and found that 41 members of the prison service were convicted in the most serious prisoner abuse trials.

But almost half of them were only handed suspended sentences. The BBC has spoken to ex-prisoners, including Makarov, about the ordeals they suffered in the Russian prison system.

The first time Makarov was tortured was in February 2020, he says. He refused to confess to a supposed plot against the prison administration and three men subjected him to continuous violent sexual abuse, he says.

“For 10 minutes they beat me, ripped my clothes. And for, let’s say, the next two hours they raped me every other minute with mop handles.

“When I fainted, they would splash me with cold water and throw me back onto the table.”

Two months later it happened again. He had been coerced into paying 50,000 rubles (£735) to his attackers and says he was raped in an attempt to keep him quiet about this.

Makarov told the BBC his prison torture had been videoed. Prisoners know the humiliating footage can be shared with the entire prison if they do not comply with the demands.

The rapists were other inmates, who – Makarov and others are certain – acted on prison bosses’ instructions.

Music would be played at full blast during torture episodes, Makarov says, to disguise the screams.

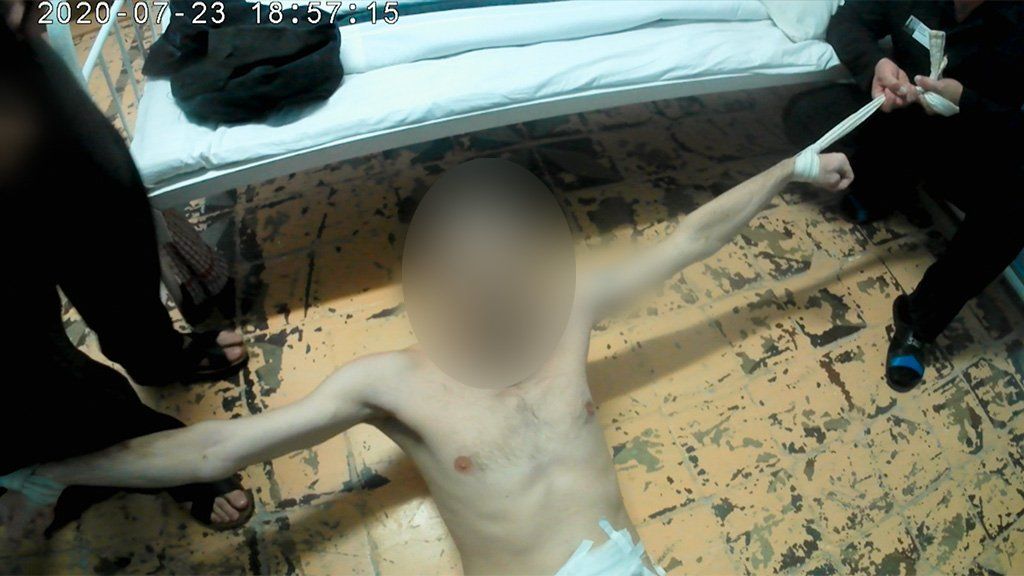

Last year’s leak of footage from Saratov was published with the help of another former inmate at the prison. Sergey Savelyev managed to smuggle out footage showing humiliation and violence against dozens of inmates. He also believes the torture is sanctioned at the highest levels as part of an organised system.

Savelyev had access to the footage because he was asked to work in the short-staffed prison’s security department. He was required to monitor and catalogue the footage from the bodycams normally worn by prison officers.

But he told the BBC that when it came to torturing a prisoner at Saratov, the officers would get inmates to do their dirty work – and ask them to wear bodycams to film to the abuse.

“I would get orders [to issue bodycams] from the head of security,” he says.

He was told to then save the recorded footage of some of these assaults to show to the security department, and on occasions transfer it onto a drive so it could be shown to more senior personnel.

After he discovered the horrors taking place behind closed doors, he started copying the files and hiding them.

“To simply walk past and do nothing is to recognise it as normal.”

In some of the clips the men carrying out the torture are seen using handcuffs – equipment, like the body-cams, that are only issued to prison staff.

Savelyev says the prisoners carrying out the abuse are, as a rule, those who have been convicted of violent crimes and are therefore serving long sentences. As such, they are interested in currying favour with the authorities in order to be treated better, he says. Such prisoners are sometimes given the nickname “pressovschiki”.

“They should be interested in doing well during this period, wanting the administration to be loyal, so that they can eat well, sleep well and have some privileges,” Savelyev explains.

Activist Vladimir Osechkin whose organisation Gulagu.net published the leaked videos, notes the chilling protocol followed by the torturers, captured in one particular clip, which suggests they are well-practised.

“They are giving signs to each other, acting in silent concert, understanding each other even without words because they are following a well-established system. [The man in shot] gives signs on how to twist or spread the man’s legs so that they can rape him.”

Following Savelyev’s leak of the evidence, six pressovschiki were arrested, but they denied being involved. Two months later the director of Saratov prison hospital and his deputy were also arrested – both denied any connection with the abuse shown in the videos.

Russian President Vladimir Putin replaced the head of the national prison service and announced that “systematic measures” were needed to bring about change. The country’s law was amended last month to introduce severe punishments for using torture as a means of abusing power or extracting evidence.

But human rights activists stress that torture as an independent offence is still not criminalised.

It is not the first time President Putin has promised change. He made a similar pledge, following the first shocking leak of such footage, in 2018, which showed guards carrying out mass beatings in a prison in Yaroslavl, north of Moscow.

Eleven Yaroslavl prison employees were given minimal sentences in 2020 and their two bosses were acquitted.

Lawyer Yulia Chvanova, who specialises in representing victims of torture, says the primary motivation for the organised abuse of prisoners is the authorities’ focus on confessions, regardless of guilt. As a result, officials responsible for investigating crime are the primary instigators of torture in Russian jails, she says.

“Confessions [are put] first and foremost.”

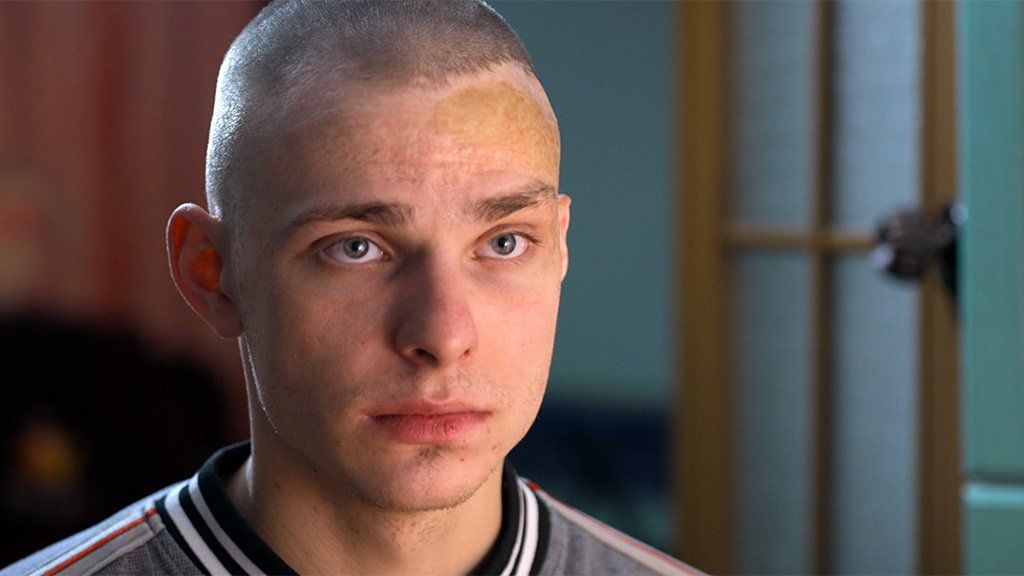

She is trying to win compensation for 22-year-old Anton Romashov, who was tortured in 2017 after refusing to admit to crimes he didn’t commit.

Romashov had been arrested for the possession of marijuana but the police were pressuring him to admit to dealing drugs – a much more serious offence. When he refused to confess, he was taken to a pre-trial detention centre in Vladimir, western Russia, in late 2016.

“I was taken to [cell] number 26. I knew exactly what kind of cell it was… because I heard screams coming from there, screams for days on end.”

There, two men were waiting for him. He says he was thrown to the floor, his hands and feet tied together behind his body, before being beaten for an entire day. When they pulled his trousers down, he said he would sign whatever they wanted. He was sentenced to five years in jail, despite telling the court that he had been tortured into the confession.

An investigation into practices at the Vladimir detention centre eventually took place after another prisoner murdered one of the pressovschiki threatening to torture him. Prison staff, asked to give statements, revealed that most of them knew what was happening in the infamous cell 26. The prison employee who was running the torture cell was convicted at a trial in which Anton and two other prisoners gave evidence.

But the biggest torture scandal in the country to date took place in the Siberian region of Irkutsk. In the wake of a protest in spring 2020 at Prison 15 in Angarsk, near the city of Irkutsk, the authorities sent in the riot squad. Hundreds of prisoners were rounded up and taken to two detention centres where prison officers were waiting with pressovschiki.

One of those who says he was tortured in the centre, Denis Pokusaev, who was serving a three-year sentence for fraud, says the prison staff were open about why they were being punished.

“[They] told me: ‘Do you think we care whether you are guilty or not? You came from a riot – so you are going to be held accountable for that.'”

Lawyer Yulia Chvanova explains the common pattern of events.

“[Investigators] decide who to interrogate, which witnesses and what investigations to conduct… They then contact the prison staff with instructions: ‘I need a confession from a particular individual.”

Pokusaev says the persecution was relentless.

“The abuse went on for almost three months every day, except weekends.”

He says staff were involved in the torture sessions.

“They laughed, ate fruit… A person is being raped with all sorts of objects… And they just laugh, they enjoy it.”

The BBC asked the Russian prison service to comment on the allegations about torture and rape in the country’s jails and detention centres. It did not respond.

Human rights activists estimate at least 350 prisoners were tortured after the riots.

Pokusaev is among around 30 men who have won the right to be legally recognised as victims in the incident and one of the few prepared to testify in court. Several trials are expected to result from the investigation. In Denis’s case, he and a handful of other inmates are soon set to give evidence against two prison employees – neither of whom have accepted the charges against them.

Yulia and all those giving testimony in the case have been made to sign a non-disclosure agreement. It is unclear whether any of the findings will lead to meaningful reform.

Pokusaev says he is still haunted by what happened to him.

“I come to a forest next to our house almost every day. And I scream obscenities, shout this all out to avoid keeping it inside me.”

But he is determined to try to get justice. He believes that is possible if people are courageous enough to speak up.

“Right now, people [in Russia] are afraid to come out and say anything… that’s why people don’t achieve anything.”

Source: BBC