Trash letters from Spanish women to Moroccan men written decades ago expose a history of forbidden topics during the colonial period.

“When will you come back to Spain?” The desperate-sounding plea had been carefully written out on the page, a sign of how important it was for Carmela.

“Tell me that you are not looking at any other women,” she wrote from Granada in 1944.

However, the man for whom these words were meant was never able to read them. Carmela’s love letter from overseas did not reach its intended destination in Morocco.

Instead, it found itself concealed in the depths of the Spanish archives, within an unexpected trove of hundreds of passionate messages exchanged between Spanish women and Moroccan men.

Confiscated during the 1930s to the 1950s, these letters document clandestine romantic relationships.

For decades, the colonial authorities of the Spanish protectorate in Morocco methodically confiscated this correspondence.

The boxes overflow with expressions of love: “I am crazy for you… I am like a goat for you,” writes a woman from Valencia.

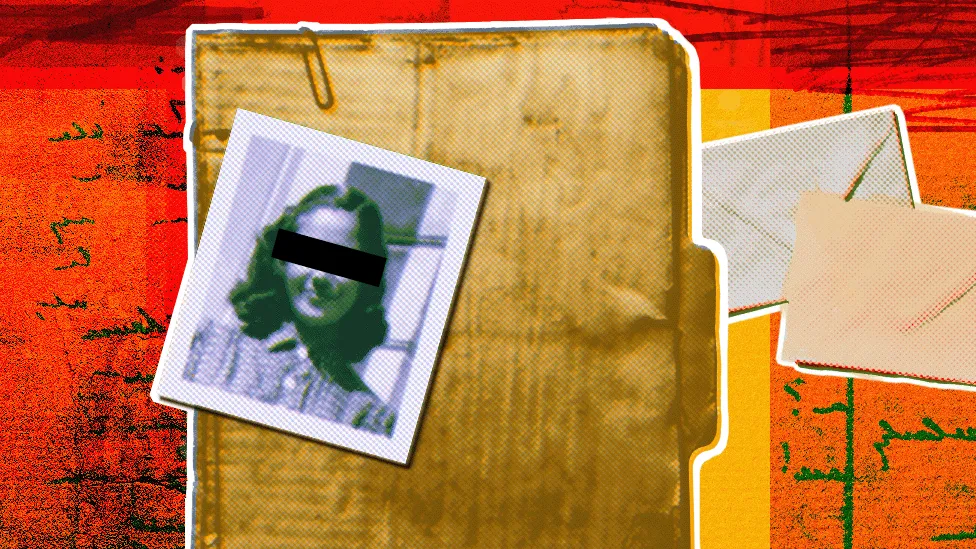

Some letters include photographs, featuring dozens of women with meticulously styled hairdos, offering glimpses of their appearance to distant lovers. One woman sent a picture of herself riding a bicycle, a candid snapshot of everyday life.

Conscientious bureaucrats filed these letters neatly into envelopes, where they were then forgotten among routine administrative documents, gathering dust until discovered and published by academics Josep Lluís Mateo Dieste and Nieves Muriel García.

Each letter provides a tantalizing glimpse into an entire relationship, shedding light on the repression faced by these connections.

Spanish officials employed various measures to thwart such relationships.

A 1937 directive stated, “As a general rule, marriages between Moroccan soldiers and Spanish women must be prevented.”

Since 1912, Spain had asserted sovereignty over a portion of Morocco as a protectorate, dividing the nation with France.

Resistance from the Berber community, notably during the protracted and brutal Rif War (1921-1926), challenged this claim, resulting in the Spanish army’s defeat by forces led by Abdelkrim al-Khattabi.

To address this, the Spanish government bolstered its troops in Morocco and enlisted thousands of Moroccans into its army.

By the 1930s, a substantial strip along the north of the country was effectively administered by Spain, with its capital in Tetouan. In 1936, General Francisco Franco, based in this territory, initiated a coup against the Republican government, marking the start of the Spanish Civil War.

In 1948, a letter was intercepted between Carmen from Zaragoza to her lover Abdeselam in Morocco. The authorities in Tetouan immediately banned both from crossing to the opposite side.

In the letter, Carmen gave news of their daughter, who would now grow up without ever seeing her father. The officials did not take the child into consideration.

Why did they regard these relationships with such contempt?

Part of the answer lies in the dictatorship’s reactionary ideology.

Franco’s government was aggressively misogynistic, rigidly controlling the mobility of women and restricting their access to employment.

It also saw itself as a defender of Catholicism, and for religious reasons, women who married Muslim men were seen as “lost to the faith”.

But the biggest single reason was what officials called “prestigio de raza”, “the prestige of the race”.

For colonial rule to continue, Spain had to be seen as superior to Morocco.

As the government understood marriage to be the subordination of a woman by a man, any marriage across the colonial divide would make a Spanish woman subservient to a Moroccan man.

If this came to be known, it would undermine the very basis of colonial domination.

By contrast, relationships between Spanish men and Moroccan women, which were plentiful in the protectorate, did not attract such extensive scrutiny and censorship as they reproduced the larger power structure of society on an intimate scale without threatening it.

This was not specific to Spain: the fear of European women entering into relationships with colonised men was common across all European colonial administrations.

In the neighbouring French zone, officials expressed similar disapproval for the political consequences of these relationships.

The Dutch in the East Indies and the British in India saw relationships between European women and colonised men as much more threatening than the reverse, and policed them accordingly.

While the range of measures to discourage these relationships went from disapproval to outright bans, the underlying rule was the same: such relationships were a threat.

These letters, however, reveal that beneath the surface of colonial society, encounters were common and led to a whole range of relationships: friendships, courtships, sexual encounters and marriages.

Opening them is thrilling – a window into lives that official documents rarely tell us about. But it is also unsettling – most letters never made it to their destination. It feels like an invasion of privacy, as these people never chose to be included in this archive.

When Morocco became independent in 1956, the protectorate government in Tetouan shut down and its archives were mostly forgotten.

They ended up mostly near Madrid, in the central archives of the administration in the university town of Alcalá de Henares where – like most of Spain’s colonial history in Africa – they were forgotten.

But despite the recent publication of some of these letters, their stories remain poorly known, and this long-forgotten archive has not yet revealed all of its secrets.