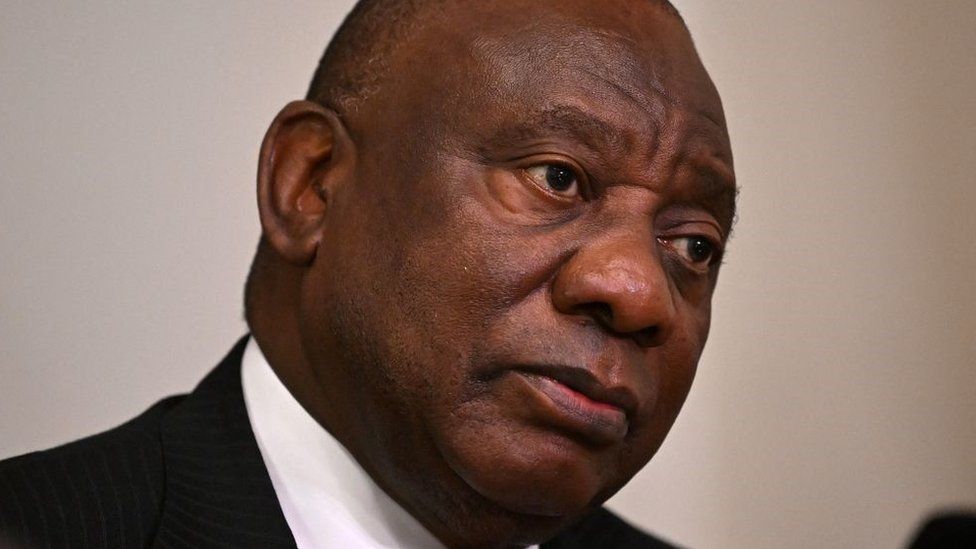

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa is fighting back after being politically harmed by allegations that he hid a large sum of foreign currency in a sofa on his game farm and then covered it up.

He has rallied his governing African National Congress (ANC) to back him in parliament, while his high-powered legal team is attempting to overturn a panel of legal experts’ damning findings against him in the biggest scandal to rock his presidency.

Former spy chief Arthur Fraser is Mr Ramaphosa’s accuser, and his allegations against the president appear to be straight out of a John le Carré novel – except that they are contained in statements he made to law-enforcement agencies and have been included in the panel’s report, which parliament will consider.

Mr Fraser alleged that a close aide of Mr Ramaphosa, Bejani Chauke, brought “large sums” of US dollars from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Morocco, and Equatorial Guinea, and, adding to the intrigue, he alleged that the aide hid the money in a couch at his home in a plush suburb in South Africa’s main city Johannesburg, before taking the cash to Mr Ramaphosa’s game farm with his “full knowledge and acquiescence”.

But in a nightmare for the president, robbers, allegedly working in cahoots with one of his employees, stole what is “speculated” to be somewhere between $4m (£3.3m) and $8m.

That is small change compared to the spymaster’s other allegation – that a whopping $20m was “moved” to a South African citizen, whom he named, after he asked police to investigate the president.

While some would dismiss Mr Fraser’s claims as nothing more than a good bed-time read, they have given Mr Ramaphosa a huge political and legal headache, as about eight bodies – including the central bank – became involved in investigations.

Mr Ramaphosa has denied any wrongdoing, and the panel – led by a former chief justice – said it could not “verify” the allegations, while “the President has rightly criticised the evidence contained in Mr Fraser’s statements as full of hearsay”.

Mr Chauke had also denied the allegations.

What Mr Ramaphosa did admit was that $580,000 had been stolen from his farm in February 2020.

While Mr Fraser alleged that this was part of the cash previously stashed in Johannesburg, the president gave a completely different version of events – that his lodge manager had sold 20 buffaloes to a Sudanese businessman on Christmas Day 2019, and this was the money stolen.

But in a blow to Mr Ramaphosa, the panel said there was “substantial doubt” that this sale took place, noting that neither the lodge manager nor the Sudanese national had confirmed this is what happened.

“We think that the President has a case to answer on the origin of the foreign currency that was stolen, as well as the underlying transaction for it,” the panel added.

It also questioned whether only $580,000 was stolen, saying the information at its disposal suggested that an apprehended suspect had confessed to stealing $800,000, while an investigator, in an audio clip, mentioned an amount of “20 million”.

“Whether the investigator was referring to US$ or ZAR [South African rand] this amount is far more than $580,000 that was alleged to have been hidden inside the sofa [at the president’s farm],” the panel said.

The panel said that in another “troubling feature”, the theft was neither reported to local police as an “ordinary crime” nor to the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (DPCI), the police unit responsible for stamping out money-laundering and organised crime in South Africa.

The panel said this was despite the fact that, in its view, the president, as the farm’s owner, was required by the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act to report it to the DPCI.

It believed there were grounds for an impeachment committee of parliament to investigate whether or not Mr Ramaphosa had committed a “serious” violation of the Act, which, the panel noted, imposes a fine or a prison sentence on anyone who fails to report a theft of more than 100,000 rand that they become aware of.

“A person who keeps huge sums of illicit money concealed at his or her house is unlikely to report the theft of such money for fear of being discovered that he or she is involved in money laundering,” the panel said.

“For this reason, the legislature considered it prudent to require any person who has knowledge of the commission of the offence of theft to report it,” the panel added.

The panel also concluded that the head of Mr Ramaphosa’s bodyguard unit, Gen Wally Rhoode, put together a team that “surreptitiously” investigated the theft, tracking down suspects in Cape Town and across the border in Namibia.

Despite this, no-one has been prosecuted or convicted of the theft, the panel’s report said, adding: “All of this occurs amid accusations of torture and bribery of the suspects to buy their silence.”

The panel also said that the information before it suggested that Mr Ramaphosa had sought the help of his Namibian counterpart, Hage Geingob to apprehend a suspect, and Gen Rhoode had travelled to Namibia as part of the investigation.

The panel said it had noted that Mr Geingob’s office issued a press statement earlier this year denying any wrongdoing on the Namibian leader’s part, but “significantly” it did not deny that President Ramaphosa had approached him.

“Nor does it deny that the request was acceded to,” the panel added.

In another damaging blow to Mr Ramaphosa, the panel went on to say that the South African leader “abused his position as Head of State to have the matter investigated and seeking the assistance of the Namibian President to apprehend a suspect”.

As if that was not enough, the panel said it appeared that Mr Ramaphosa had “thrust himself into a situation where there was a conflict of interest between his official responsibilities as the Head of State and as businessperson involved in cattle and game farming” and he had “acted in a manner that was inconsistent with his office”.

As a result, the panel felt there were sufficient grounds for parliament to establish an impeachment committee – which would have the power to subpoena witnesses, and documents – to carry out further investigations, before deciding whether or not the president should be removed from office for endangering “our constitution and the rule of law”.

“The authority to impeach is deeply rooted in the principle of accountability,” it said.

However, Mr Ramaphosa has challenged the panel’s report in South Africa’s highest court, the Constitutional Court, with his lawyers describing it as “unlawful” and saying it should be annulled.

And in a sign of his strong position in the ANC as he seeks a second term as party leader later this month, its top leadership body has ordered its MPs, who form a majority in parliament, to vote against the report’s adoption because of the court case.

The law states that a president can be impeached only if his alleged violations of the constitution and law are “serious”.

Mr Ramaphosa’s many supporters will be hoping that South Africa’s most senior judges rule in his favour, and, at most, he is accused of minor transgressions.

As for the stolen money, its current whereabouts are unclear.

Namibian police reported – according to the panel – that they had identified bank accounts, lodges, houses and vehicles suspected to have been purchased with the proceeds of the crime, while Mr Fraser alleged that Gen Rhoode had “seized” cash in Namibia, although the president’s main bodyguard has “emphatically denied that he investigated the theft of money”.

The plot thickens.