Unable to get a job as an accountant since graduating five years ago, Ghanaian Nathaniel Qainoo has been forced to swap his calculator for a spanner.

The 29-year-old was busy repairing a taxi under the shade of a mango tree when the BBC met him at his home in the small town of Kasoa, about 30km (18 miles) from the capital Accra.

He often spoke of “the hardship” – a phrase that has become common in Ghana since the nation plunged into a deep economic crisis in 2022.

This was the year when the government defaulted on its debt repayments, international rating agencies downgraded Ghana’s creditworthiness to “junk status,” and inflation skyrocketed to 54%. To add to the woes of Ghanaians, their currency, the cedi, has lost 70% of its value in the past eight years.

This forced Ghana to secure a $3bn (£2.4bn) bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The economic recovery efforts have been costly, resulting in significant losses for pensioners and investors who held government bonds.

All this has made Mr. Qainoo so despondent that he does not intend to vote in Saturday’s presidential and parliamentary elections, though the electoral commission is confident that voter turnout will be high.

“I don’t know how this country is going to be saved from this crisis,” Mr. Qainoo told the BBC.

His mind is on emigrating to North America or Europe.

“I would like to leave the country, go outside, live better, work harder,” Mr. Qainoo added.

He is not alone. Many young people – who make up almost 40% of the population, according to the 2021 census – want to quit Ghana.

They see few job prospects in a country with an unemployment rate of 14%.

So it is not surprising that the economy has dominated the election campaign.

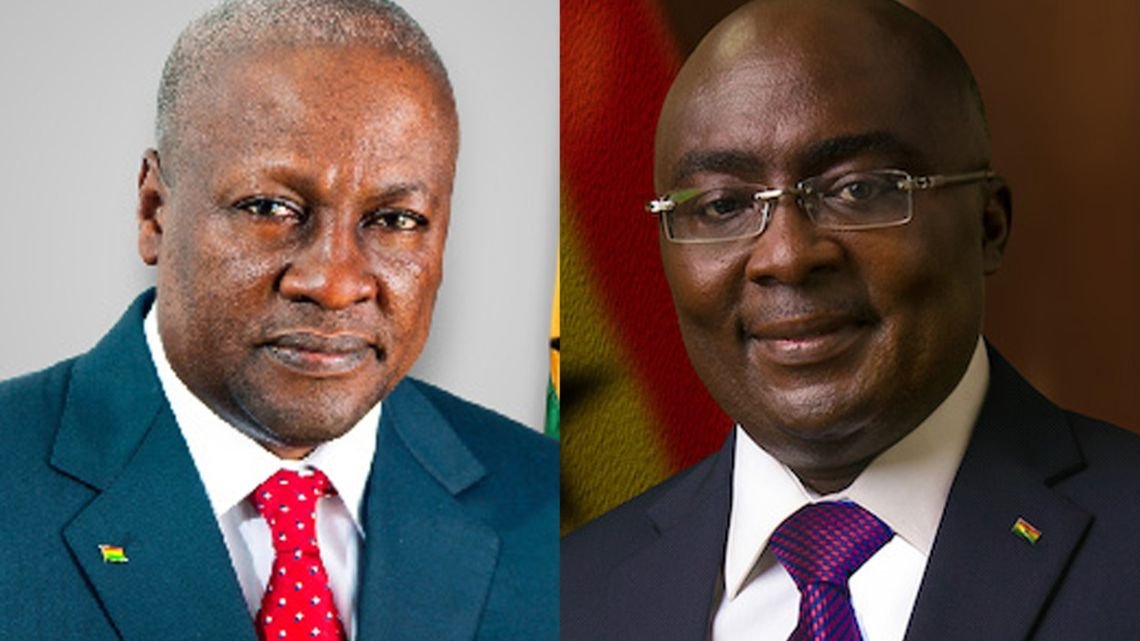

The two main presidential front-runners are:

• Former President John Mahama, who is hoping to barrel his way back to power like Donald Trump, and

• Mahamudu Bawumia, who feels the time has come for him to step into the president’s shoes after eight years as vice-president.

The two are vying to succeed President Nana Akufo-Addo. He is stepping down at the end of his two terms, with Ghanaians hoping for a smooth transfer of power to ensure that Ghana retains its reputation as a stable democracy.

Contesting the election under the banner of the governing New Patriotic Party (NPP), Bawumia’s major handicap is incumbency.

Holding a master’s in economics from the UK’s prestigious Oxford University, he heads the government’s economic management team, and the collapsing economy has tarnished his reputation as an “economic whizzkid.”

He was mocked in 2023 as “our Maguire” – a reference to Manchester United footballer Harry Maguire, who had been performing badly on the pitch at the time.

On the campaign trail, Bawumia preferred to call himself “the driver’s mate” – a phrase used in Ghana to describe a commercial vehicle driver’s assistant, as he sought to distance himself from decisions taken under Akufo-Addo’s watch.

“We may be tired of hearing it, but there is no avoiding the fact that the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war resulted in the greatest economic depression in the world since the 1990s with most countries recording negative GDP growth,” he said.

Bawumia has criss-crossed the country in a blue-coloured bus, with his image emblazoned on it alongside his campaign slogan: “It is possible” – a reference to the fact that he can win and stimulate economic growth.

No party in Ghana has ever won more than two consecutive terms since the country restored democracy in 1992, a tradition the NPP says it is determined to break by ensuring that it wins a parliamentary majority and Bawumia the presidency.

The centrepiece of his campaign is a promise to create a “digital economy,” with skills training for one million young people in a bid to put a dent in the unemployment rate.

“Dr. Bawumia’s government plans to invest in a digital economy hub and provide venture capital funding for tech start-ups,” his campaign website says.

“This will include creating innovation hubs, providing regulatory incentives, and supporting tech entrepreneurs with mentorship and business development resources,” it adds.

Ghanaian political analyst Clement Sefa Nyarko told the BBC that Bawumia’s promise to create a “digital economy” was his biggest electoral drawcard.

“Bawumia has transitioned from being a so-called economic whizzkid to a digitalisation champion and I think that’s one of the big things he is riding on,” Dr. Nyarko said.

“In fact, if you see his posters in town, he has this symbol of digitalisation, suggesting that he is the man to take Ghana forward,” he added.

As for Mahama, his campaign has focused on a promise to “reset” the economy, with the essence of his message being, as Dr. Nyarko put it: “Give me a chance. At least the economy didn’t crash under my watch despite the difficulties.”

But his critics have doubts, pointing out that Ghana plunged into an electricity crisis when he was in office from 2014 to 2017, so they do not see how a man who could not keep the lights on can reset the economy.

This – along with the fact that his government was dogged by corruption allegations, which he dismissed as politically motivated – led to him failing to win a second term in 2017.

The power cuts were so bad that Mahama joked at the time that he was known as “Mr. Dumsor” – dum means off and sor means on in the local Twi language.

In this campaign, Mahama – the flagbearer of the National Democratic Congress (NDC) – has promised to make Ghana a “24-hour economy” through the creation of night-time jobs in both the public and private sectors.

“All the major and most prosperous economies in the world operate various degrees of 24-hour economies.

“They include the United States, where nearly 30% of the labour force work at night; the United Kingdom (19%); Germany (12%) and France (7%). In Africa, Kenya is contemplating a 24-hour economy,” a document outlining his economic strategy says.

In order to ease the cost-of-living crisis, both candidates have also promised to scrap some taxes, including the much-criticised electronic levy on mobile transactions and the levy on the carbon emissions produced by petrol or diesel-powered vehicles.

Economist, Prof. Godfred Bokpin told the BBC it was unclear how the two candidates would fulfil their promise as it would create a “fiscal gap,” at a time when Ghana was under an IMF-backed economic recovery programme that required the government to increase its revenue and slash expenditure.

“They will face a challenge in terms of navigating within the IMF-supported programme,” he added.

Political analyst, Asa Asante told the BBC that he expected a close race between Mahama and Bawumia.

“Politics is nothing but a contest of ideas and a referendum of your work. People are going to see which one will really work the magic and of course what are their records,” he added.

The political odds appear to be in Mahama’s favour, with an opinion poll released on Monday by Global InfoAnalytics giving him 52% of the vote to Bawumia’s 41.3%.

But with the poll having a margin of error of 1.9%, some analysts say Mahama could fall short of crossing the 50% mark, forcing a run-off.

Bawumia’s campaign team has dismissed the poll as skewed, saying they are confident of propelling him to the presidency on Saturday – and making history by giving Ghana its first Muslim president.

DISCLAIMER: Independentghana.com will not be liable for any inaccuracies contained in this article. The views expressed in the article are solely those of the author’s, and do not reflect those of The Independent Ghana.

Source: GhanaWeb